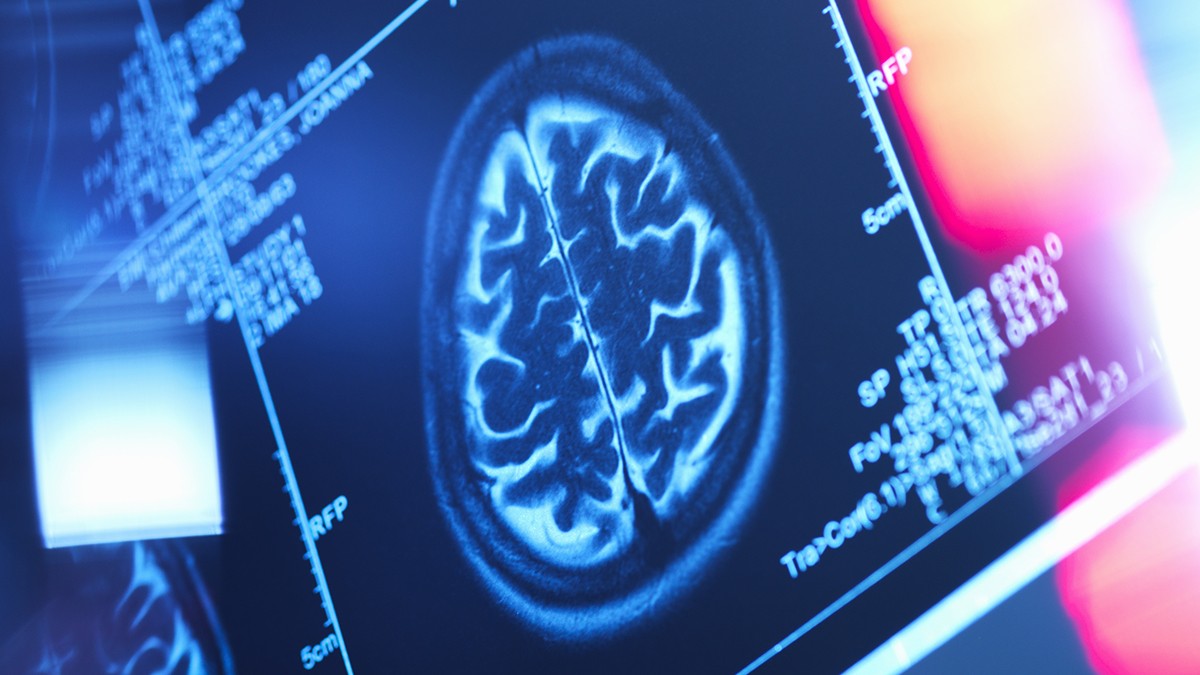

Carrying excess body fat isn’t just a matter of weight – where that fat accumulates is now linked to accelerated brain aging and cognitive decline. New research from Xuzhou Medical University in China analyzed MRI scans and cognitive data from nearly 26,000 individuals, revealing that specific fat distribution patterns are independently associated with reduced brain volume, neurological risks, and faster cognitive deterioration.

The Study’s Key Findings

Researchers used statistical modeling to categorize participants into six groups based on body fat distribution. The results were stark: all groups with varying fat patterns showed lower brain volumes and less gray matter compared to lean individuals, even those with average BMIs. This suggests that traditional BMI measurements alone don’t fully capture the risk to brain health.

Two previously undefined fat distribution types stood out:

– “Pancreatic-predominant”: High fat concentration around the pancreas.

– “Skinny-fat”: Dense fat deposits around organs, despite a normal BMI.

Both profiles correlated with the highest risk of gray matter loss, white matter lesions, and accelerated brain aging. The study also found sex-specific links: brain aging accelerated more in men, while the pancreatic-predominant pattern was more strongly associated with epilepsy in women.

Why This Matters

This research reinforces the idea that obesity isn’t just about total fat mass; it’s about where the fat is stored. Previous studies have shown that higher BMI can harm brain structure, but this work suggests that fat distribution itself may be a separate risk factor. The findings could mean that individuals with seemingly “healthy” BMIs might still be at risk if they carry excessive visceral (organ-based) fat.

“Brain health is not just a matter of how much fat you have, but also where it goes,” says radiologist Kai Liu.

Caveats and Future Research

The study’s findings are based on a single snapshot in time. Fat distribution and brain health weren’t tracked over years, so cause-and-effect isn’t proven. The participants were also middle-aged and primarily from the UK, limiting generalizability.

However, the research points to a crucial area for future investigation. If validated in larger, more diverse studies, these fat profiles could become early warning markers for cognitive decline. This could empower individuals to make lifestyle changes or seek medical intervention sooner.

The more we learn about this link between fat and brain health, the better we can target treatments and prevent neurological problems.