Scientists have successfully sequenced the complete genome of a 14,400-year-old woolly rhino using a remarkably preserved piece of flesh found inside the stomach of an ancient wolf pup. This unprecedented feat of paleogenomics provides critical insight into the rapid extinction of this Ice Age giant, pointing strongly towards climate change as the primary driver.

The Unlikely Source of Ancient DNA

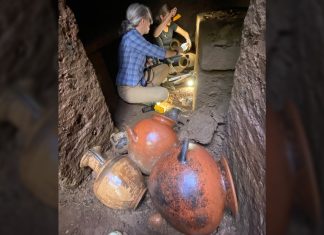

The woolly rhino (Coelodonta antiquitatis ) tissue was recovered from the mummified remains of a wolf pup discovered in Siberian permafrost in 2011. An examination of the pup’s last meal revealed it had consumed the remains of one of the last woolly rhinos to walk the Earth. Researchers then extracted, sequenced, and analyzed the rhino’s full genome from the partially digested muscle tissue.

“This is the first time a full genome has been recovered from an extinct animal found inside another animal,” explained Camilo Chacón-Duque, a bioinformatician at Uppsala University. The study, published in Genome Biology and Evolution, details the process and findings.

Genetic Stability Until the Final Decline

The research team compared the newly sequenced genome to previously obtained genomes from woolly rhinos dating back 18,000 and 49,000 years. They found surprisingly consistent levels of genetic diversity and inbreeding across all three samples. This suggests that the woolly rhino population remained relatively stable in northeastern Siberia until shortly before its extinction around 14,000 years ago. The implication is that the species did not decline slowly due to gradual inbreeding, but rather suffered a swift collapse after a period of prolonged viability.

Climate Change, Not Hunting, as the Key Factor

Previous research has debated whether human hunting or climate change caused the extinction of large mammals like the woolly rhino. This new study reinforces the climate hypothesis. The woolly rhino persisted for 15,000 years alongside early humans in northeastern Siberia, indicating that hunting pressure was not a decisive factor.

Study co-author Love Dalén explains: “Our results suggest that climate warming, rather than human hunting, caused the extinction.” The findings align with a period of rapid warming known as the Bølling-Allerød interstadial (14,700 to 12,900 years ago). This dramatic shift in climate likely eliminated the rhino’s preferred vegetation, leading to a rapid decline in the species.

Implications for Future Research

The success of this study demonstrates the potential of analyzing DNA from unexpected sources. Researchers now hope to apply this technique to other fragmented or degraded samples, unlocking new insights into the past.

“It was very challenging to extract a complete genome from such an unusual sample, but it opens up possibilities for analyzing DNA from other unlikely sources,” said Sólveig Guðjónsdóttir, a researcher at Stockholm University.

The ability to recover genetic information from ancient predator-prey relationships provides a powerful new tool for understanding the dynamics of extinction and adaptation in the face of environmental change.