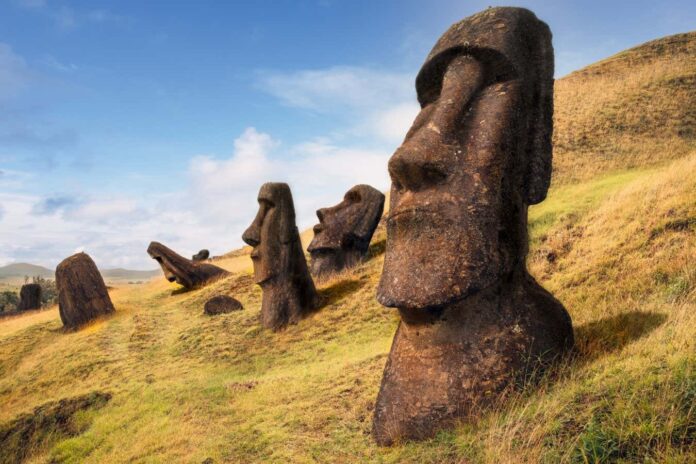

Easter Island’s iconic stone statues, or moai, were likely built not by a unified, top-down command, but through a decentralized system of competitive display between independent communities. New high-resolution mapping of the island’s main quarry, Rano Raraku, suggests that multiple groups carved these massive monuments using distinct techniques—not as a singular effort directed by powerful rulers.

The Quarry Reveals Decentralization

Archaeological evidence points to a complex society on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) starting around AD 1200, populated by Polynesian seafarers. For decades, there has been debate over whether the hundreds of moai were coordinated by a centralized authority.

The latest research, led by Carl Lipo at Binghamton University, used drone technology to create a detailed 3D map of Rano Raraku, the sole source of volcanic rock for the statues. The team identified:

- 426 unfinished moai at various stages of completion

- 341 trenches outlining carving blocks

- 133 voids indicating successful statue removal

- 30 separate work areas, each with unique carving methods

This division suggests that the moai creation wasn’t a unified project but rather a fragmented process where individual communities competed to create the most impressive monuments. Combined with prior evidence suggesting small teams could move the statues, this paints a picture of decentralized ambition.

Challenging the Collapse Narrative

The traditional narrative of Easter Island’s decline often blames centralized leadership for deforestation and societal collapse due to overexploitation of resources. However, if moai construction was community-driven rather than top-down, it shifts the blame away from megalomaniacal leadership. Instead, the island’s environmental issues may have stemmed from competitive carving rather than centralized mismanagement.

“The monumentality represents competitive display between peer communities rather than top-down mobilisation,” says Lipo.

Debate Persists Among Researchers

Not all experts agree with the decentralized interpretation. Dale Simpson at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign argues that the clans on Easter Island were more interconnected than Lipo’s team proposes, and collaboration was likely essential for stone carving. Jo Anne Van Tilburg at UCLA also cautions that further research is needed before drawing definitive conclusions.

The debate highlights a core question: Was Easter Island’s moai culture a display of collective ambition under strong leadership, or a testament to independent competition?

The Bigger Picture

The moai debate matters because it forces us to re-evaluate how ancient societies organized large-scale projects. If Easter Island’s monuments arose from competition rather than control, it suggests that similar dynamics may have shaped other cultures. The island’s story may not be one of collapse due to centralized failure, but of a resilient society driven by decentralized, competitive spirit.