The connection between the heart and the brain is more critical than previously understood, with new research suggesting that the brain’s reaction to a heart attack may actually worsen the damage. Experiments in mice demonstrate that suppressing nerve signals from the injured heart to the brain improves cardiac function and reduces scarring, opening new avenues for treatment.

The Heart-Brain Connection Explained

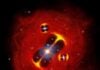

For decades, heart attacks have been viewed primarily as a mechanical problem — a blocked artery cutting off blood flow. However, this study reveals that the nervous system plays a crucial role in the recovery process. When the heart suffers damage, it sends signals to the brain via the vagus nerve, triggering a response that can amplify inflammation and impede healing.

Specifically, researchers identified TRPV-1 positive neurons as key contributors in this pathway. These nerve cells become hyperactive after a heart attack, relaying “damage” messages to the brain. Shutting down these neurons in mice led to:

- Improved heart pumping ability

- Reduced scar tissue formation

- Enhanced electrical stability of the heart

This is significant because it demonstrates that the body’s natural inflammatory response, while initially necessary for tissue removal, can become detrimental if prolonged or dysregulated.

Inflammation’s Role in Recovery

The signals from the heart travel to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (a brain region controlling stress, blood pressure, and heart rate) and then to the superior cervical ganglion in the neck. This ganglion, a cluster of nerve cells, shows heightened inflammation after a heart attack, releasing pro-inflammatory molecules called cytokines. Reducing this inflammation in mice directly improved cardiac function and tissue repair.

Why this matters: The nervous system doesn’t just react to a heart attack; it actively participates in the outcome. If the inflammatory response is unchecked, it can transition from a protective measure to a self-destructive process.

Future Treatment Strategies

The findings suggest that therapies targeting the brain-heart pathway could revolutionize heart attack recovery. Researchers propose potential approaches, including:

- Vagus nerve stimulation: Modulating nerve activity to reduce inflammation

- Gene-based therapies: Targeting specific brain regions involved in the response

- Immune-targeted treatments: Controlling inflammation at its source

While these strategies are still in early stages, the study provides a clear roadmap for future research. According to Vineet Augustine, a neurobiologist at the University of California, San Diego, “We can now start thinking about therapies that go beyond the heart.”

The inflammatory response is not inherently negative; it is essential for tissue removal and repair in the early stages. However, when excessive or prolonged, it can hinder recovery.

The U.S. sees roughly 805,000 heart attacks each year, according to the CDC. Understanding the brain’s role in these events could lead to more effective treatments and improved outcomes for millions of patients.