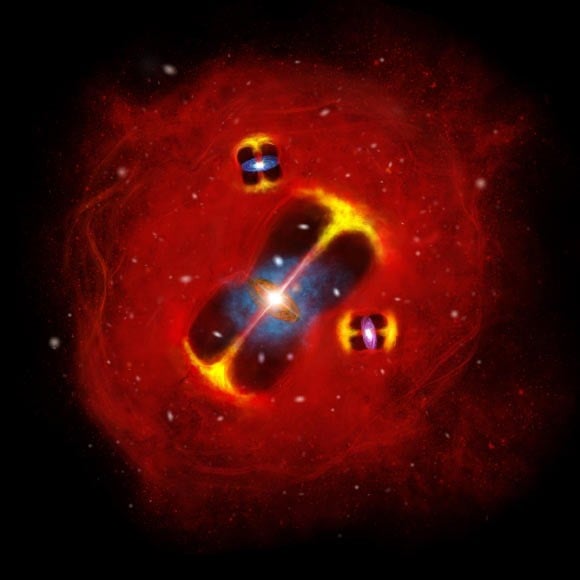

Astronomers have detected unexpectedly hot gas within a distant, developing galaxy cluster just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang. This discovery, made using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), challenges existing models of how galaxy clusters form and evolve in the early Universe. The protocluster, designated SPT2349-56, is located roughly 12.4 billion light-years away, meaning we observe it as it existed when the cosmos was only a tenth of its current age.

The Unexpected Heat

The observations reveal an extremely heated atmosphere surrounding the cluster’s core, which contains multiple actively feeding supermassive black holes and over 30 galaxies undergoing intense star formation. These galaxies are birthing stars at rates up to 1,000 times faster than our Milky Way, all packed into a space only three times larger.

“We didn’t expect to see such a hot cluster atmosphere so early in cosmic history,” explains Dazhi Zhou, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of British Columbia. Before this, scientists assumed that early galaxy clusters were too young to have fully developed hot, stable atmospheres.

Thermal Sunyaev-Zel’dovich Effect

The breakthrough came through the use of the thermal Sunyaev-Zel’dovich (tSZ) effect, a technique that detects the faint shadow cast by hot electrons in galaxy clusters against the afterglow of the Big Bang – the Cosmic Microwave Background. This indirect method allowed astronomers to map the hot gas without needing to observe light emitted directly from it.

Implications for Cluster Formation

The discovery suggests that massive clusters may form more rapidly and violently than previously thought, with powerful outbursts from supermassive black holes injecting enormous energy into the surrounding gas. The study proposes that these energetic processes, combined with intense starburst activity, can rapidly overheat the intracluster gas in young clusters.

This overheating is likely a critical step in transforming these early, cool clusters into the sprawling hot structures observed today. Current models of galaxy and cluster evolution may need revision to account for this accelerated heating process.

A New Laboratory for Cosmic Evolution

SPT2349-56 presents a unique opportunity to study the earliest stages of cluster formation. The coexistence of rapid star formation, energetic black holes, and a superheated atmosphere in such a young, compact cluster is unprecedented.

“SPT2349-56 is a very strange and exciting laboratory,” Zhou emphasizes. “There is still a huge observational gap between this violent early stage and the calmer clusters we see later on.” Mapping how these atmospheres evolve over time will be a key focus for future research.

The findings, published in Nature on January 5, 2026 (doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09901-3), push the boundaries of what astronomers can study in the early Universe and open new questions about the interplay between supermassive black holes, galaxy formation, and the evolution of cosmic structures. The earliest direct detection of hot cluster gas ever reported forces scientists to rethink the sequence and speed of galaxy cluster evolution.