New research reveals that the movement of Earth’s tectonic plates – specifically the rifting where plates pull apart – has been the primary driver of long-term climate shifts over the past 540 million years. This challenges the long-held assumption that volcanic activity from colliding plates was the dominant factor in regulating atmospheric carbon and global temperatures.

Historical Climate Fluctuations and Carbon’s Role

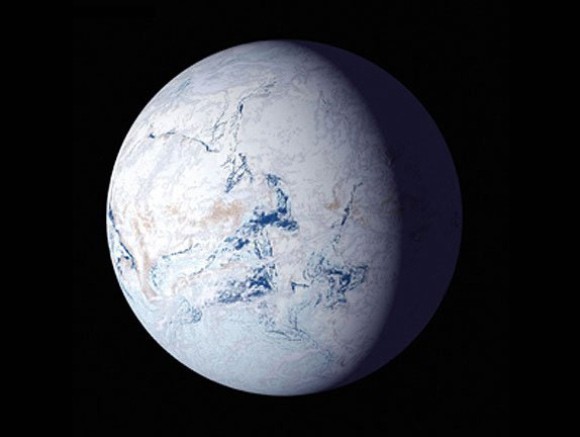

Earth’s climate has cycled dramatically between extreme “icehouse” conditions (cold, glacial periods) and “greenhouse” states (warm, high carbon dioxide levels) throughout its geological history. Notable icehouse periods occurred during the Late Ordovician, Late Paleozoic, and the Cenozoic era. Conversely, warmer periods consistently coincided with increased atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations.

The study, led by University of Melbourne researcher Ben Mather, reconstructed how carbon moved between volcanoes, oceans, and the Earth’s interior over hundreds of millions of years. This analysis shows that carbon released from mid-ocean ridges and continental rifts – where tectonic plates separate – likely drove major climate transitions for the vast majority of Earth’s history.

Challenging the Volcanic Paradigm

For decades, scientists believed that volcanic chains formed by colliding tectonic plates were the primary source of atmospheric carbon. However, Mather’s team found that volcanic emissions only became a dominant carbon source within the last 100 million years.

“Our findings show that carbon gas released from gaps and ridges deep under the ocean from moving tectonic plates was instead likely driving major shifts between icehouse and greenhouse climates for most of Earth’s history.” – Dr. Ben Mather

This suggests that the fundamental mechanism for climate regulation has been plate rifting, not volcanic collisions, for most of Earth’s past. By integrating plate tectonic reconstructions with carbon-cycle modeling, the researchers traced how carbon was stored, released, and recycled as continents shifted.

Implications for Current Climate Change

The research underscores the critical role of carbon in driving long-term climate shifts. The study highlights that current human activities are releasing carbon at a rate far exceeding any natural geological process observed in the past.

This means that the Earth’s climate system is being destabilized at an unprecedented speed. The findings add to a growing body of evidence that atmospheric carbon levels are a key trigger for major climate swings, and that the scale of modern climate change is deeply unusual.

The study serves as a stark reminder that understanding how Earth controlled its climate in the past is crucial for interpreting the alarming speed of change today.

The research was published in Communications Earth & Environment.