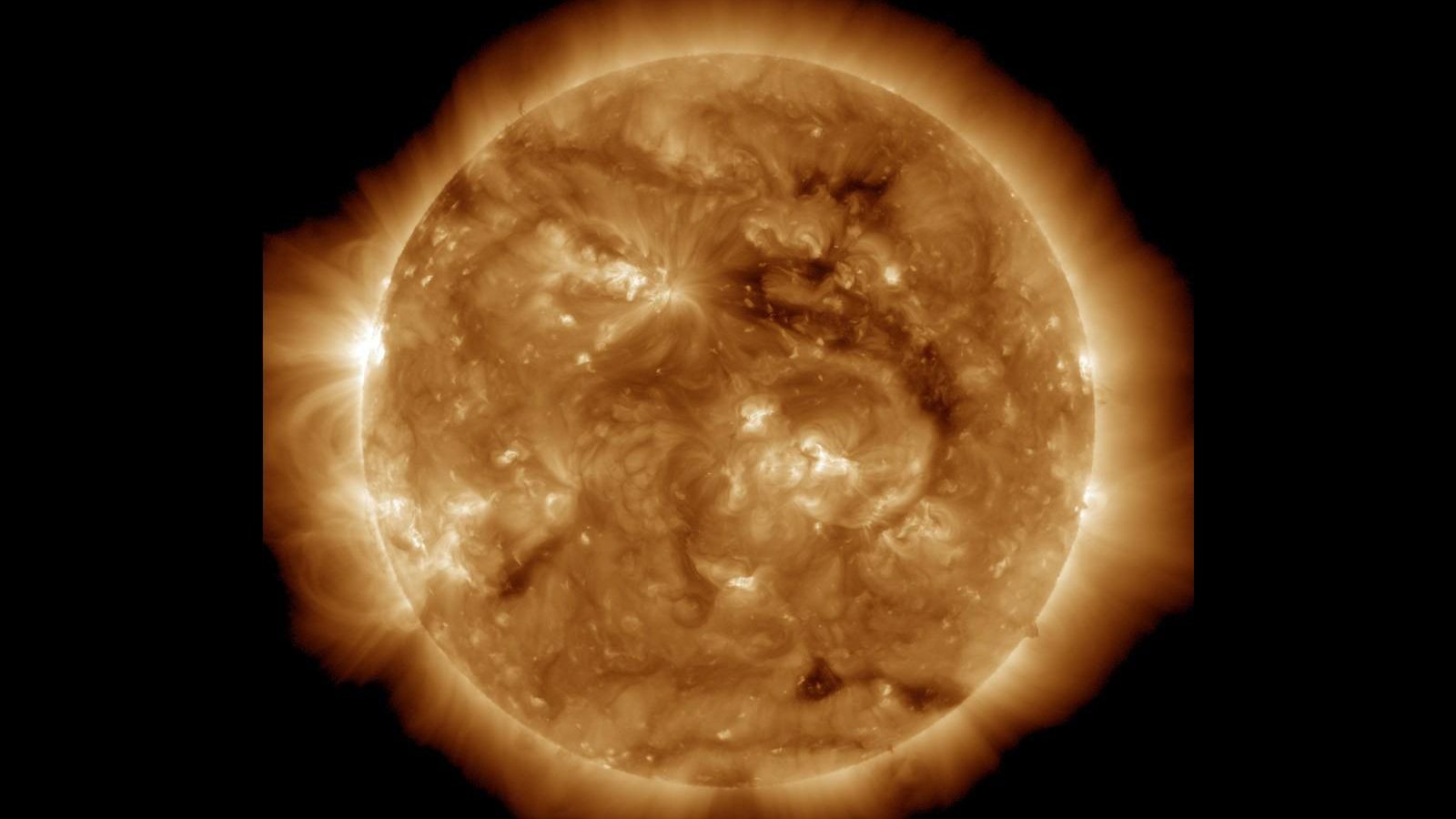

For decades, scientists have puzzled over a significant paradox: how the sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona, is vastly hotter – millions of degrees – than its visible surface, which is around 9,932 degrees Fahrenheit (5,500 degrees Celsius). Now, using the world’s most powerful solar telescope, researchers have observed twisting magnetic waves, a discovery that could help unravel this long-standing mystery.

The Discovery of Torsional Alfvén Waves

The research team, using data from the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii, has directly observed small-scale magnetic twists on the sun – specifically, torsional Alfvén waves. These waves, predicted in 1942 by Swedish Nobel laureate Hannes Alfvén, are magnetic disturbances that travel through the sun’s plasma, a superheated, electrically charged gas. While larger versions of these waves have previously been linked to solar flares, these smaller, constant twisting waves have remained elusive until now.

“This discovery marks the end of a decades-long search for these waves, with origins dating back to the 1940s,” stated Richard Morton, a professor at Northumbria University in the U.K., who led the study.

Why These Waves Matter: The Solar Heating Puzzle

Scientists have long suspected that these small-scale waves could continuously transfer energy from the sun’s surface into its atmosphere. This process would power the solar wind and, critically, heat the corona to its incredible temperatures. The results offer strong support for theoretical models attempting to explain how magnetic turbulence carries and dissipates energy within the sun’s upper atmosphere. Having direct observations allows researchers to now test these models against what they actually observe.

Unprecedented Observations of the Sun

To arrive at their conclusions, Morton’s team utilized the Inouye Solar Telescope, which captures the highest-resolution images of the sun ever achieved. The telescope’s four-meter width allows detection of faint shifts in light, revealing how plasma flows through the corona in unprecedented detail.

During the telescope’s commissioning phase in October 2023, the team tracked iron atoms heated to an astounding 1.6 million degrees Celsius and observed faint red and blue shifts on opposite sides of magnetic loops. These shifts are the hallmark signature of twisting Alfvén waves.

The Technique: Spectroscopy and Hidden Motion

The twisting of the sun’s magnetic field lines is subtle, making it difficult to detect directly in images. Therefore, the team employed a technique called spectroscopy, which measures how hot gas moves toward or away from Earth. This motion subtly alters the light’s color – red when moving away, blue when moving closer – thus revealing the concealed twisting pattern within the sun’s atmosphere.

“The movement of plasma in the sun’s corona is largely dominated by swaying motions,” explained Morton. “I had to develop a way of removing the swaying to isolate and identify the twisting.”

The Results: Constant Motion and Energy Transfer

The findings reveal that even in the sun’s most tranquil regions, the corona is filled with torsional Alfvén waves. These waves constantly rotate the sun’s magnetic field lines, transporting energy upward through the solar layers. This transport of energy from the lower atmosphere into the corona ultimately results in heat release, providing new insights into the mystery of the sun’s corona being significantly hotter than its surface.

For Morton and his colleagues, this long-sought detection opens up new avenues of investigation into how these waves propagate and ultimately dissipate energy within the corona.

The discovery represents a significant step forward in understanding the complex dynamics of the sun and its atmosphere, promising to shed light on one of the most enduring puzzles in solar physics.